Chloe Lee, a National Cathedral School student, and Sammy Miller, a student at St. Albans School, each received an All Hallows Guild environmental scholarship of $1000 to go toward appreciation and understanding of the outdoor world. Please enjoy their reports reprinted below.

Chloe Lee attended the Horticultural Science Summer Institute (HSSI) at NC State University

This past summer, through the generosity of the All Hallows Guild, I had the incredible opportunity to attend the Horticultural Science Summer Institute (HSSI) at NC State University. There, I learned so much about the field of horticulture and agriculture over the course of a week, with topics ranging from propagation, fruit and vegetable production, landscape design, and more.

On the first day, we got an overview of the program, as well as some agricultural challenges we would be tackling throughout the week. Afterwards, we got to meet our suitemates and counselors, and we potted succulents together as a relaxing way to start the week and to get to know each other.

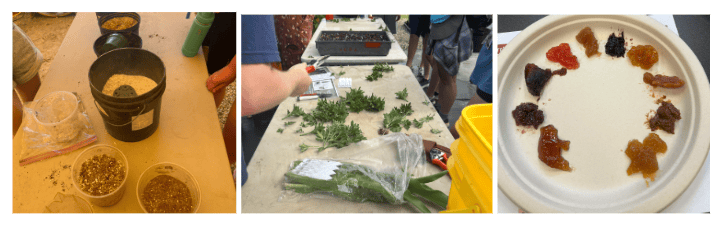

On our second day, we woke up bright and early to travel to the J.C. Raulston Arboretum, where we received a tour and a lesson on plant cuttings. We learned how to properly propagate leaves and grasses—cutting below the node for leaves and in an arrow shape for grasses—and even took home our own cuttings. Later that morning, we learned about post-harvest physiology, learning how flowers like zinnias and eucalyptus absorb nutrients and maintain freshness. I was surprised to learn that Sprite can actually be used as a floral preservative due to its makeup of sugar and citric acid. We then experimented with substrates, discovering how different materials can affect plant growth and profitability. That afternoon, we toured the Plant Sciences Building at NC State, where researchers demonstrated how drones and AI can be used to count strawberries and monitor crop health, and we made “pH indicator beads” from red cabbage juice. We ended the day with a jam tasting led by Dr. John Dole, sampling his experimental fruit jams. The jams we tried were all unique types of fruit, most of which I had never heard of before, like rosella, maypop, and cocona. My personal favorite was his prickly pear jam!

The next morning, we visited the Kornegay Family Farm, where we learned about the commercial production of sweetpotatoes. I found it fascinating how nothing goes to waste—while perfect sweetpotatoes are packaged for sale, larger or blemished ones are pureed, canned, or turned into fries. I also learned that sweetpotato should be spelled as one word (to distinguish it from regular potatoes, which are a different plant species). Later, at Brooke’s Fresh Cut Flower Farm, we saw how horticulture intersects with business and aesthetics: her farm primarily grows flowers for weddings and offers flower subscription services. In the afternoon, we rotated through five stations focused on vegetable production,

studying soil composition, nutrient levels, and irrigation systems. We also practiced pest management by identifying thrips on pepper plants and exploring wood trunks for insect damage. To end the day, we made botanical soap using lye, palm oil, and natural dyes like red clay and charcoal.

On Wednesday, we toured the Central Crops Research Station, where we learned about North Carolina’s major role in sweetpotato production (North Carolina is the number one producer of sweetpotatoes in the US!) and sampled six different varieties, including the popular Covington. We also explored an experimental orchard with fruits like figs, pawpaws, persimmons, and peaches. We spent the rest of the day propagating ferns, lilies, and carnivorous drosera plants; learning about genetics by cross-pollinating petunias; and finally, arranging our own floral designs using flowers we had collected earlier in the week.

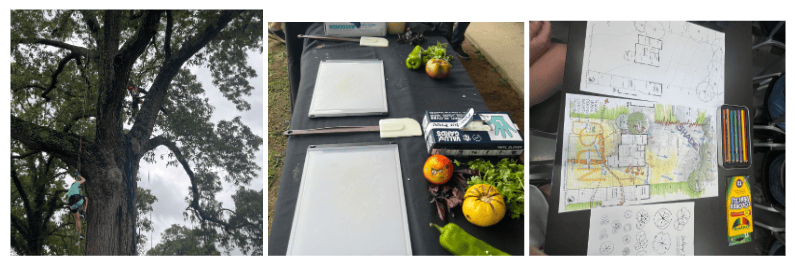

Thursday began at the Lake Wheeler Research Field Labs, where arborists from Bartlett Tree Experts demonstrated tree climbing and discussed their work in arboriculture. Then, we all put on harnesses and climbed a massive tree to experience how they work with their own trees. Afterwards, we made fresh pico de gallo at the Agroecology Farm using freshly picked tomatoes, basil, garlic, and other ingredients. In the afternoon, we visited Greenview Landscape Design, where we learned how landscape architects create functional yet beautiful spaces. My group designed a pollinator-friendly garden, incorporating native plants to attract bees and butterflies. Our final evening activity was unfortunately rained out, so we got some extra downtime to spend with our campmates during our final night at NC State.

On the final day, we returned to the Arboretum to discuss college and career paths in horticulture before giving short presentations on our favorite experiences from the week.

Attending HSSI was an unforgettable experience that deepened my appreciation for horticulture’s scientific and creative aspects. I gained hands-on skills in propagation, design, and plant care, but I also came to understand horticulture’s broader role in solving global issues, whether through sustainable agriculture, ecological landscaping, or crop innovation. Beyond the technical knowledge, I learned the value of collaboration and curiosity, and how even seemingly small innovations, like adjusting soil composition or breeding new plant varieties, can have lasting impacts on communities and ecosystems. Thanks to the support of the All Hallows Guild, I not only strengthened my passion for plant science but also found a community of people equally dedicated to cultivating a greener, more sustainable future.

Sammy Miller backpacked in the Cascade Range of Washington State

For the past two years I have worked as a “Weed Warrior Leader” in Rock Creek Park, organizing invasive species removals among St. Alban’s students and working alongside Rock Creek’s National Park Service Botanist, Ana Chuquin to spread awareness about what community members can do to have a lasting impact on their environment. During my backpacking trip to Washington State, I aimed to apply what I had learned beyond my local environment, testing my ecological knowledge, observing unfamiliar landscapes, and comparing environmental management practices. Besides wanting to further my efforts in invasive removal, I also wanted to challenge myself by testing my wilderness skills by embarking on the longest and hardest backpacking trip I’d ever been on. The trip was eight days in total, with five of those days being in the wilderness with only our forty-pound packs to survive the fifty mile through hike. One of my other goals in recounting the journey is to examine how immersive wilderness experiences deepen environmental understanding and personal growth.

Our first two days were spent in a pretty typical drive-in campsite in Marblemount, WA about thirty minutes from the Thunder Creek Trailhead. Even though we had not even begun the official backpacking portion of our trip, the nature already differed so much from anything on the East Coast. Tall Douglas firs, western red cedars, and hemlocks were the three main types of trees we saw throughout the entire trip.

On our second day, we hiked to Doubtful Lake which was a ten-mile out and back where we climbed through a forest, up an alpine ridge, and over a scree field in order to catch a view of Doubtful Lake. I decided to do this hike without my pack in order to save energy for the arduous week ahead of me. Along the route, I observed how plant communities shifted with elevation: in the sub-alpine forest, the same three tree species prevailed, but higher up, mountain hemlocks became more common; the narrow spires blended with firs making them more adapted to colder, wind-exposed conditions. Once we broke out of the forest, we soon entered into a massive alpine meadow. I immediately noticed an array of wildflowers that blanketed the meadow. When I looked closer I could confirm that many of the plants actually were native wildflowers; however, a majority of the meadow was covered in a bright purple, signifying the presence of spotted knapweed, or centaurea stoebe.

Spotted knapweed is one of the two most problematic invasive species in the North Cascades. Originating from Eastern Europe, knapweed arrived in America on ships transporting contaminated seeds. Its pink-purple thistle flowers made it unmistakable, and its dense spread illustrated how completely a single invasive can dominate a fragile alpine ecosystem. The plants survives in dry climates, making the North Cascades and it’s wildfire ridden environment a perfect target. Throughout the meadow, I couldn’t help but notice how densely the knapweed covered the trail and other plants. I was seeing how the invasive knapweed out-competed native plants for sunlight and water. In addition to out-competition, knapweed also releases toxins into the soil to kill native plants, reduces feeding options for wildlife, accelerates erosion by pushing out deep-rooted natives, and acts as perfect fuel for wildfire due to it’s density and flammability. Knapweed also spreads quite easily, as it’s seeds are viable for eight years. In this specific area, seeds were most likely spread through snowmelt and foot traffic from hikers.

The National Park Service uses a variety of methods to control invasives in the North Cascades, some of which are similar to what I had done in in Rock Creek and some that I had not seen before. On the third day of the trip, I stopped by the North Cascades National Park ranger station to pick up my backcountry camping permits as well as my bear canisters as I would be going into the park later that day. However, before I left, I struck up a conversation with two rangers about what invasive removal looks like in the park and how it differed from Rock Creek. North Cascades has 225 contains non-native plant species, forty of which are targeted invasive species. The main difference I discovered between Rock Creek and North Cascades was the need for heavier removal methods than simple volunteer work in North Cascades. The rangers explained that the parks Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program was developed under the National Environmental Policy Act which combines herbicide use and ecological modification with supplemental manual removal work. Compared to Rock Creek, it seemed like North Cascades uses much more herbicide and industrial based methods, which makes sense due to the scale of the park, the distance from a major population center, and the lack of large volunteer force.

Our first wilderness day took us from the Thunder Creek Trailhead to Tricouni Camp, an eight-mile hike that was a teaser of what it’d be like carrying full packs. Each forty-pound pack carried the essentials for five days like food, shelter, and basic gear. Some additional items I carried were a jetboil stove and water filter, arguably the two most important items. The first day proved to be mostly flat walking, so we didn’t ascend into any alpine ecosystems, but it was the first time we would see an old growth grove on the trip. About halfway through the hike, I first encountered a small grove of old-growth Douglas-firs, some estimated to be more than a thousand years old. These remnants of pre-industrial forest reminded me how rare such stands are after nineteenth-century logging.

Wilderness day two was fourteen miles from Camp Tricouni to Camp Buckner which took a total of thirteen hours. The biggest takeaway from this day was the effect that the dramatic elevation changes had on the ecosystem around me. The first half of the day was spent in the lowland forests, marked by the three main tree species that create a temperature-regulating canopy. Here, densely vegetated clearings appeared intermittently, some deliberately cut to reduce wildfire spread. While effective, such clearings often invite invasive regrowth; along the trail, I saw crews using machetes and targeted herbicides to manage these outbreaks. The second half of the day, we ascended up to Park Creek Pass where the ecosystem rapidly changed from lush, dark green forests, to alpine meadows with smaller trees, more wildflowers, and more sunlight. Plants in the alpine zone grow closer to the ground to avoid wind and conserve heat. These plants help prevent erosion in the glacier filled mountain ranges. Park Creek Pass was also where I was first able to observe some of the fauna in detail. Marmot’s, large ground squirrels, littered the rocky pass. These animals move up into the mountains during the summer months to feed on wild berries and plants in order to build thick layers of fat for the winter.

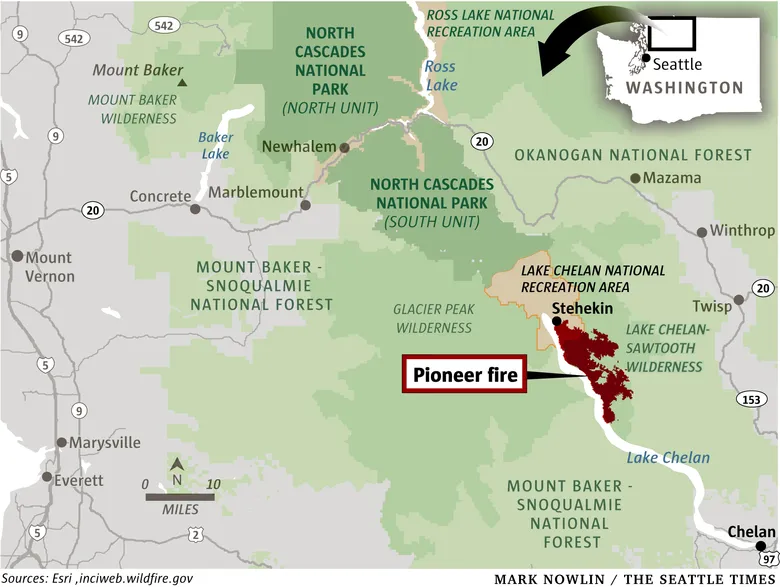

The third wilderness day was from Buckner Camp down the Stehekin River Valley to Basin Creek. We followed the Stehekin River whose surrounding area was severely affected by the Pioneer Wildfire which, in 2024, burned nearly 40,000 acres over five months and came close to the isolated community of Stehekin. I experienced almost five miles of nothing but burnt trees and vegetation along the river, the effects still very present and visible. Witnessing the landscape firsthand revealed that wildfires, rather than invasives, are the region’s dominant ecological threat, the opposite of my experience in Rock Creek. In the Stehekin Valley, residents now face heightened risks of erosion, runoff, and renewed ignition, and it will likely take a decade before new forest growth stabilizes the area.

The fourth day marked our final push to Sahale Glacier Camp, which lays at the base of Boston Peak and Sahale Glacier. The last two miles of this day exhibited an ecosystem unlike anything I had ever seen. We were completely above treeline, but there was still plenty of vegetation such as moss, shrubs, and small berries that thrived in the wet climate. The hike up to Sahale Glacier was filled with sightings of mountain goats, which park rangers describe as “ecosystem engineers.” The goats are known to lick and expose mineral-rich rocks so other species can use them. Though non-native, the goats play a vital role by redistributing minerals and nutrients across alpine terrain.

As we neared our campsite, the ground level vegetation slowly disappeared and gave away to rock and fields. We camped at roughly 8,000 feet of elevation, beside the glacier that feeds into the same Stehekin River we followed earlier. Besides being the source of the river itself, the glacier is important for the river valley ecosystem as it regulates water temperature, providing a safe habitat downriver species. However, the glacier has lost 25% of its volume in the last twenty years, a clear warning of the consequences of climate change.

Our final day was a short hike out of the park which consisted of the same trails that we used to get up the glacier. As we descended back below the cloud and tree lines, I was able to reflect on all of the biomes I had encountered on my trip. From lowland forests to alpine meadows, each zone was connected and dependent on the others, showing how fragile the Cascade ecosystem really is in the face of climate change.

Coming into this trip, I had hoped to mainly compare invasive species in the Cascades vs Rock Creek. While I accomplished that, the later stages of the trip revealed details about broader environmental issues in Washington that I had no concept of back home. First, speaking with park rangers and witnessing the massive meadows of invasive knapweed made me realize the scale of the issue in larger national parks compared to Rock Creek. This meant pesticide use replaced volunteer work; however, possible ways to get the community involved in the fight against invasives would be hosting educational sessions on how to identify invasives or hosting local fundraisers that would be put to use by the NPS for staffing and pesticide supply, both of which have taken a hit after the recent $1 billion budget cuts.

Secondly, seeing the effects of wildfires and glacial retreat firsthand made me realize how uneducated many of us are when it comes to these issues back on the East Coast. What felt distant to me before the trip had already started to affect communities in the West, and will be affecting all Americans in the close future. Mass-scale education about the effect that climate change and its sub-consequences will have on our lives in the very near future. I would like to use my experience on this trip as well as more research I will do to host education sessions for those who may not understand the gravity of climate change and what is going on in the Western United States.